|

From the Italian Art Encyclopaedia 2013

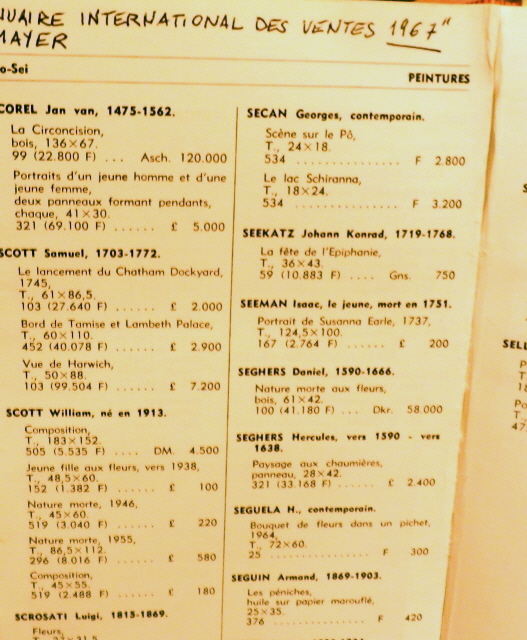

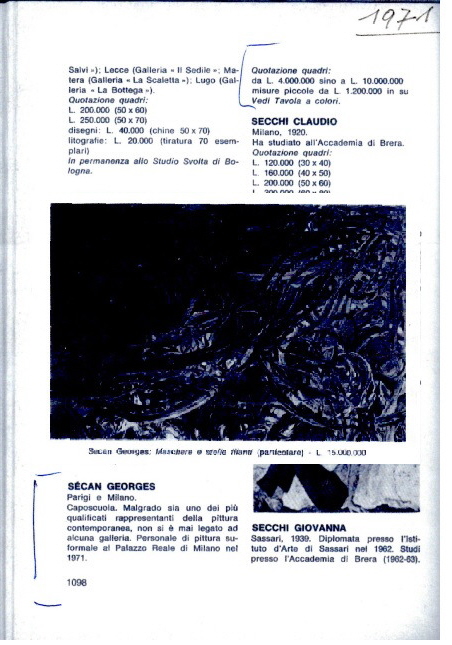

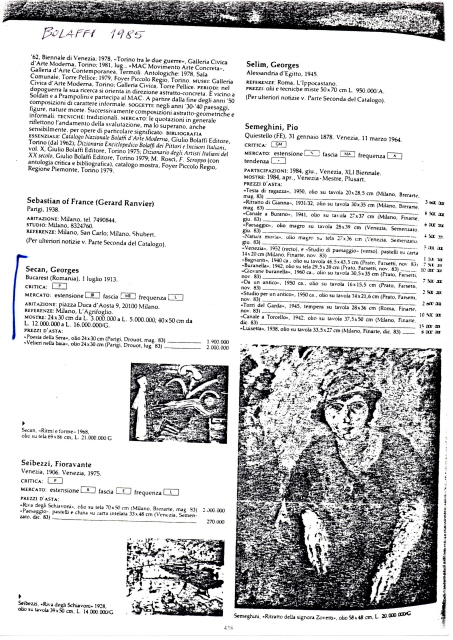

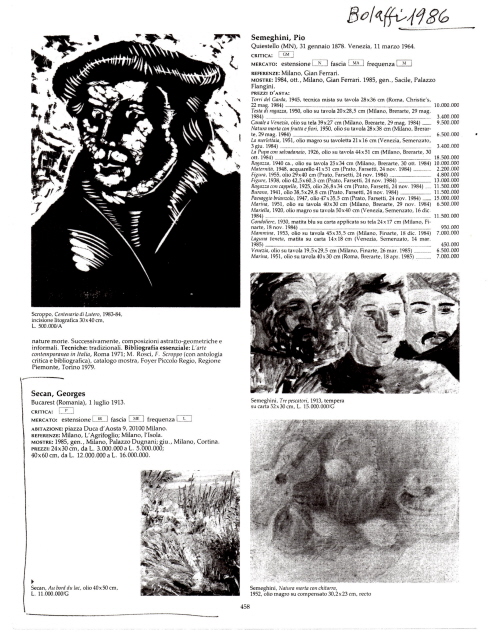

SÉCAN Georges

G. Sécan (1913-1987) was born in Bucharest, the

son of a French vice-consul and a Finnish woman.

He studied Fine Arts in

Paris and

Munich,

getting several awards and winning important

competitions since he was eighteen.

He

lived

for

long

periods

in many European and

extra-European countries, gaining

experiences

which

left

deep marks in his pictorial work. On

many occasions he was inpired also by Italian

landscapes. Remaining out of the main artistic

currents

as well as

of the galleries

and

art

merchants’ world, he has

however

succeeded

in

achieving an

international

reputation

thanks

to

the widespread success

earned among

the best

critics

and

among

the general

public.

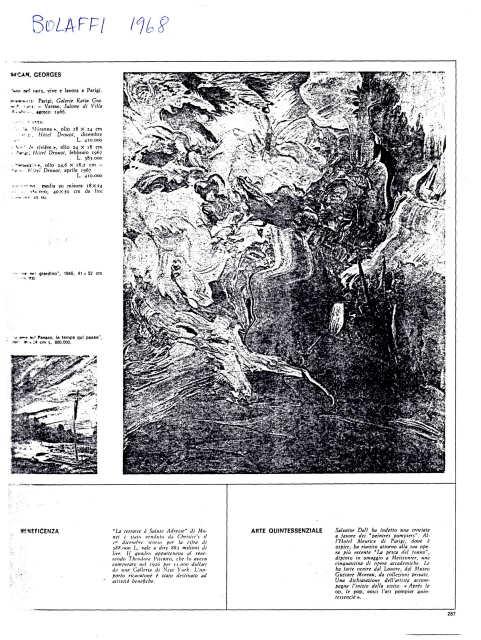

In 1941, he created

a new kind of painting

that

he called «

Subform ».

Tapié redefined « Subformel » that

kind of painting in which the artist tends to

express himself straying completely from

himself,

In

the

attempt of

finding

again

a lost

ancient

tune, the

one

of the primitive man

in

front of

his simple and truest subconscious.

Sometimes,

that

engagement

leads to

a transfiguration of

the landscape or

simply of

a rhythmic sensation

into

images

whose

extreme

expressive violence,

as well as

the dazzling

intensity

of

colours,

has few comparisons in contemporary painting.

VALUE

This

great

artist,

who

died

over 25 years ago,

has

never

had

art merchants

or

Galleries

as reference, certainly because of disagreements

he suffered in his youth with the

above-mentioned art operators.

Thus it becomes nearly

impossible to give a correct economic evaluation

to this excellent master’s work.

We

can only remember that, in the 70s, in the

period when Sécan was invited

for a one-man

exhibition at Palazzo Reale

in

Milan,

immediately afterwards

Picasso,

the value

of his

works had internationally reached notable

figures.

|

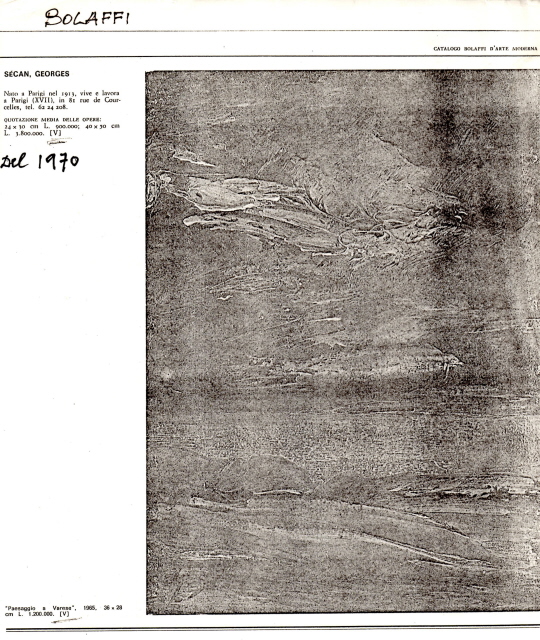

From the UTET

Encyclopaedia

Georges Sécan,

French painter (1913), was born in Bucharest to a French

father (the then Vice-Consul in Bucharest and a Finnish

mother. He studied art in Paris and Munich, winning various

awards and important competitions from the age of 18

onwards. A wandering spirit, he has sojourned at length in

countries in and outside Europe, including India, the Sudan

and Egypt. The experiences he gained from his journeys have

left profound traces on his painting. On numerous occasions

Sécan has also found inspiration in Italian landscapes.

Whilst remaining apart from the main

artistic currents ( although the recall to expressionism is

not out of place), as well as from the world of galleries

and art dealers, Georges Sécan has nevertheless attained

international fame as the result of the open praise on the

part of both the most important critics and the public,

thanks to his prestigious exhibitions.

With a warm

and vigorous brush-stroke, and an exceptional sense of

colour, Sécan is the creator of a new genre of painting

which, in 1941, he called “Subform” ( forms let loose from

the profound subconscious). Tapié, on the occasion of an

exhibition organized for Sécan by the Municipality of Milan

at Palazzo Reale, redefined this kind of painting “

Subformel” in which the artist tends to express himself by

his complete detachment from himself in the attempt at once

again finding an ancient, lost understanding that of

primitive man faced by his simple and truer subconscious.

This commitment is sometimes translated in the

transfiguration of the landscape ( a sunset, a sea-bed) or

simply by a rhythmic sensation images of an exasperated

expressive violence which, like the blinding intensity of

the colour, have few equals in contemporary painting.

Georges Sécan

– European Enciclopedia ed.Garzanti

Georges

Sécan ( Bucharest 1913), French painter. After studying in

Paris and in Munich, after a figurative beginning, yet

already attentive to abstract influences, he left Europe

and, in India, he came in contact with Zen philosophy,

which led him to deepen his researches of

“self-contemplation”: that way, there were born the

psychological presuppositions of a painting which, in

1941, with a notable advance on the informal vague, he

presented like subform painting ( forms sprung from the

subconscious) At its roots there is a condition of ataraxy,

meant as a mastery of a psychical store, a sort of vital

surplus operatively transferred into an extremely vehement

colouristic and visionary surplus ( Precivilization, 1961,

Lausanne, Musée des Beaux Arts): it’s a technique which,

if on one hand it seems to approach Sécan to the so-called

abstract expressionism and to Cobra Group – which, at a

certain point, he seemed to get near – it actually differs

from them, because of its stating as authentic revelation

of the subconscious, the element which distinguishes Sécan

also from Surrealism ( seen as automatic recording of

Freud’s individual repressed instincts ) and rather

connects Sécan - in his mediation between East and West –

to the world of archetypes populating Jung’s collective

unconscious. Thus Sécan’s work alternates themes ranging

from the art of portrait to musical notations, from

Eastern landscapes to the series of “marionettes”, which

the artist painted in Paris after the war, as a dramatic

note picked among Europe’s ruins.

From the Universal Encyclopedia SEDA

A first-rate personage in the current

artistic view, perhaps Sécan represents one of the most

precious examples of that cultural internationality able to

give a determining incentive, on the poetic and human plan,

to the historical community of the great cycles of art. All

Sécan’s life runs through a thick intertwining of events, of

journeys, of meetings. Become famous while still very young,

with great sacrifices and not few disillusions, he had to

conquer the inestimable richness of his freedom. In fact,

after bitter experiences, he decided to make his demanding

pictorial speech advance, in a totally autonomous way,

beyond the ambit of galleries. From that always renewed

determination, his spirit progressively gained that

consciousness and that rigour which very soon claimed the

most qualified critics’ attention and the most exigent

public’s one. A very highly-cultured man, friend of the

greatest artists of our time, Sécan gave birth to a series

of pictorial cycles which coincide with the various phases

of his restlessness travelling, as philosophical messages

and as expressive sensitivity. In the space of his very

productive activity we can number the paintings inspired by

the Buddhist philosophy, direct result of his stays in

India; the canvases dedicated to Eastern themes, conceived

in Sudan; the series of marionettes, dramatic annotation

picked among the ruins of Europe after the war; the cycle of

moral paintings, which ranges paintings supplied with a

timing device starting a carillon ; the series of

“Reactions” ; the space-temporal researches.

"I know I have found new and original

accents for my painting, searching another self in myself,

trying out further layers of subconscious, primordial,

rudimental, metaphysical ones, completely unrelated to the

usual vision of the psyche – layers which don’t reconnect

anymore to us since millennia. From this marvellous journey

through the realm of spell, - an unperceivable almost

abstract heritage – I, moved and upset, get original

impulses, uncanny expressions, new visions, in the land

beyond myself. " ( Georges Sécan)

Georges Sécan, French composer and painter ( Bucharest,

1913). He studied Art of Painting at the Julian Academy in

Paris and, for music, he was a pupil of G. Enesco’s ( violin

and composition). Together with his main

activity as a painter, - he will cultivate successfully,

also later, the passion for music. He published many works

favourably welcomed not only by the public, but also by many

great musicians of our time: among his most appreciated

works, we mention Bizarre Dances, a Trio in D

Major, a Brilliant Fantasy, this last one

dedicated to Yehudi Menuhin.

(Encyclopaedia of Music, ed. Curcio)

( from the book “ Subform Painting” by G.

Sécan, published by Garzanti )

Art-Life by G.Sécan

Art is projection of life. To speak of my

painting, I have to speak of my life, my way of thinking.

It is often thought that a painter is a

profligate, a libertine who delights in searching for the

most dissolute amusements among debauchees in Bohemian

circles. I have never been part of such a group, and my

life, starting from my adolescence, has been dedicated to

ideals of virtue, to artistic and philosophic interests,

rather than to material things. It is useless to recall

here, as I did in “ Mes Confidences”, the times when I used

to meet Brâncusi, Picasso, Braque and others who had not yet

become the “ monstres sacrés” of our days, or the bizarre

“combines” of the art market.

I have never felt like following a style

or a way of life which was not compatible with my own

idealistic conviction. So I have not only remained almost

always isolated from painters, their circles and trends, but

I have also avoided any connections with dealers and

important art gallery owners, despite their insistent

requests, simply for the love of my own freedom and my own

ideas.

At 16, I think I can say it, I was

already a painter: my paintings were liked, and I was

considered one of the best at the Académie des Beaux-Arts

Julian in Paris.

Without interrupting my studies at the

Académie, I obtained work teaching art in a girls' convent -

boarding school – and later, because I was reliable and my

students achieved excellent results, I had other pupils to

whom I gave private lessons. I was alone, however, without

friends or relations, incapable of organizing myself; and

if, as sometimes happened, my lessons were paid several days

later, or if I did not succeed in selling a painting, I

would go without food for days. Another cause of worry for

me was always trying to appear tidy and respectable, with

clean, neat clothes, especially when I lacked the minimum

necessary for food. But I did not give up, I succeeded in

overcoming the difficulties. I was a supreme optimist, and

did not want to submit to the requirements of the gallery

owners. The only thing I had was my freedom ( which also

meant isolation). My thoughts detached me from a practical

side of life, from reality, and the idea of being provident

was foreign to me.

When I sold my works the money only

seemed mine if I spent it, especially to buy books, and I

soon had no money left. In addition to my great passion for

art, I felt myself drawn to seek for something beyond

myself. If I painted outside, in front of an inspiring

landscape, I abandoned myself to prolonged meditation,

allowing my glance and my spirit to wander beyond the limits

of the horizon. I felt that art gave me the sense of a

truer existence that overcame the artist, stimulating me to

a more profound life, to a “ surplus” of the mind. I loved

to read books of ancient Greek philosophy and I was

frequently assailed by metaphysical problems..

Often, waking in the middle of the night,

I remained for a long time in the dark, trying to understand

the mystery of Creation and, as I wrote then, “what this

existence so firmly attached to me, this ‘I’ on which I

depended blindly, hid under its stranger’s mantle “. I

found only one reply to my distressing problems: “Life is

nothing, man is nothing, all is closely linked to Nothing. A

supreme Nothing which, despite its right to ‘be’ before

anything whatever, was inconceivable, could not exist except

attached to Everything”. Thus, I thought that the law of

Equity – Nothing-Everything – remains in force for all

eternity.

These were thoughts that tormented me,

notwithstanding my faith in God, while in the great and

cruel city of Paris I was perhaps one of the poorest and

most solitary student of the “ Beaux – Arts”.

Moreover, I had to live hidden from my

family since they would have taken me back into the fold and

prevented me from following my vocation as a painter. I

had to try never to be noticed by the police or by anybody

else since I was a minor who had left home without his

parents’ consent, without documents. I had always to make a

good impression, hide my poverty. I did not live like other

young men, and dancing, amusements, girls, and taking part

in the hair-raising parties of my fellow students seemed

prohibited things to me in those days of study, philosophy

and deprivations.

My thoughts were of little interest to my

companions at the “ Beaux-Arts”, who busied themselves with

the galleries and critics, and a calculating search for a

successful style. Further more, they already had their own

habits, amusements, friendships, families and I was still “

the foreigner” even though I was French like them.

In order to achieve a life which was

truer to myself, more authentic, to subtract myself from

stupid officialdom, the grip of false and servile

conventions, and the dealers who promoted only their own “

stables” of painters, I decided, in view of possibly

abandoning Paris for long voyages, to perfect as far as I

could my painter’s craft. I may now say that, thanks to

this decision, I soon succeeded in making a name for myself

as a painter without the help of any gallery or any dealer.

Rather, little by little, deceived and deluded by an

avaricious gallery owner, I developed a kind of rancour for

all of them, including the honest ones, and subsequently I

have never agreed to alter my ideals for then, to sacrifice

my dreams, to allow the cold and mechanical practicality of

astute market organisations to make any impositions on my

visions as an artist.

This had an infinity of consequences in

my life. But from the artistic and human point of view,

this determination was precious to me. I have found

propulsive forces in myself, in my passion for art.

And this is why I have never allowed

gallery owners or dealers to handle my work.

Already isolated by my ideas from my

colleagues and from the galleries, solitude began for me

with all its bitterness, even before I started out into the

world. And, curious destiny, it has lasted an entire life,

without family, home, affection, always and everywhere like

a foreigner.

And my fate of being a solitary and a

stranger continued thus for all a lifetime: from Paris to the

many, many other cities where destiny took me. However,

being passionately interested in philosophy, I also learnt

to detach myself from myself, first with ataraxy – a serene

state of mind, protected from perturbation – and then, with

that kind of Zen which I derived from it, to paint, and to

isolate myself in some way from any noisy atmosphere in

which I might find myself and from the onset of

preoccupations.

Circumstances led me, after Paris, to

spend a great part of my life in the Orient. My shy and mild

character, inclined to tolerance, yielded still further to

its tendency to respect and love of my neighbour, and to

generosity which unfortunately has also brought be much

grief.

It is difficult for those who have never

lived in the East to understand how, especially with an

artist’s sensibility, if one is not pessimistic or irascible

or too egocentric, in those places one feels oneself

naturally attracted towards the virtues and values of

goodness, towards the beneficence of thought, and that

remarkably precious something that is true altruism. Perhaps

one is able metaphysically to receive more elevated and

spiritual messages from a hotter sun and a bluer sky that

the usual skies of Europe. In those gardens which are always

green, with that sun which exalts life, there was something

intoxicating in the air stimulating one to do good.

In the years when I was a painter artist

at King Farouk’s Court, I was in great demand by the most

important families as a portrait painter, and success and

money enabled me to live well. I became involved in many

charitable institutions, and among other things I was an

active member of the Committee of the Heliopolis-Cairo

Orphanage. When one has not assimilated the ways of thinking

and feeling which prevail almost everywhere in the East, how

absurd certain situations seem which are the result

precisely of their fatalism, of spirit of submission and an

excess of oriental indulgence! A lot of problems occurred to

me just because I had been influenced by the environment. I

became fond, from among other children, of a little girl who

was not yet three, taciturn, always ill and who walked with

difficulty whose mother, although of Italian origin, worked

during the war in the bars and other places frequented by

the Allies. Her daughter lived in such an unsuitable

environment for a child that I decided to do something about

it.

Later, as time passed, I came to

recognise, that what I had done for the child and her mother

had never created the least sign of gratitude in them but,

on the contrary they both caused me grief and shame. I

only found consolation and refuge in art and in solitary

meditation. This existence of mine in pensions and hotels

finally came to an end when I married in 1972. For the first

time I found the sense of comfort given by having a home and

family which, after a difficult life, have granted me a

happiness until then unknown.

However, it is true that for me solitude

was a source of meditation and concentration. Even more than

my life itself, it was my thoughts which gradually led me to

subform painting. Having finished my studies at the Académie

des Beaux-Arts Julian, I spent a year in Munich to perfect

them and then returned to Paris. There, thanks to the

generous Rothschilds and to Waldemar George, the most

authoritative art critic of the time, my works soon became

sought after.

Whilst painting a landscape I avoided

technique and skills in order to allow myself to be

penetrated and inebriated at length by the sense of mystery

and the boundless sky, trying to paint only in reaction to

intercepted sensations, in the studio I abandoned myself to

abstract painting, I left myself be guided by fancy,

impulses, feelings of the moment, not without searching in

myself, anxious to intercept and record on the canvas some

sensorial perception, key to our human condition, the enigma

of existence.

It was from my painter uncle that I

learnt to look better into myself. In a corner of his studio

he kept a poster on which was written “Try to be yourself”,

a saying of which he often reminded me. It impelled him to

be more attentive to the impulses of his soul than to

technical skills. Thus this precept so dear to my uncle

spurred me on, little by little, to seek for the real

meaning of being.

What led me, however, to more complete

introspection was reading Epictetus’s famous manual. These

maxims for living which were held in such esteem by Marcus

Aurelius, Pascal and Napoleon, made my existence less

precarious spent, as it was, almost entirely between one

country and another, with that feeling of a person isolated,

of a “stranger” (“tubab” as I was called in Senegal, or else

“European” in India, or “Kharedji”, “ostaz” or “huaga” in

other countries).

It was the Manual, modified in accordance

to my artist’s sensibility in order to avoid the stoics’

egocentricity, which led me to that imperturbable state of

mind, the ataraxy, which proved so influential in my moral

artistic formation.

I believe that interior research does not

only serve to deepen our faculty of thinking, but enriches

the soul with new perceptive faculties and gives us an

extreme degree of receptivity.

From childhood, as I often heard said, I

liked to look for a long time at the starry sky, and my

first desires were to posses the moon, the stars and the

trees. Perhaps this is why at one time trees were rarely

absent from my landscapes, not so much as a link between

earth and sky, but as a psychic liberation, or as a gesture

of rebellion.

As I have already said, I have always

looked for a reason in the mystery of the Creation. The

Bible and mythologies say that “…first there was chaos”,

identifying chaos, space, with Nothing. For me, space was

not in fact Nothing, but rather, in its so simple and

authentic essence it was one of the most extraordinary

structures of the Universe: it served as a container for

anything whatsoever.

In my adolescent mind, I convinced myself

that all things in nature conformed to a kind of dialectical

Equilibrium, to a sort of “Equity”, and that our most exact

sciences with their infallibility, so often demonstrated and

re-demonstrated, had developed in accordance with this

rule. I realized that Everything inclined towards Nothing,

that it became entwined with Nothing. The Yes with the No,

the definite with indefinite, the before with the after. An

affirmation always existed as a function of its own

negation, as happens with every life, for each specific

thing. And if the Universe mirrors its Creator,- I

ingenuously thought – also He, avoiding usurpations, ought

to be composed of two equal forces, in dialectical

opposition: “the Creator-non-Creator”, the Lord of Yes and

the Lord of No.

Thus, in this union of opposites in which

everything is annulled, I asked myself would it not be more

natural if there were only the absolute Nothing in the world

in all its supreme purity? But how could that which is

non-existence itself be made to exist? A Zero-space would be

necessary, which could not contain the least thing either in

itself or near to it, and a Zero-time so that it might

endure in eternity not bound to the present or the future.

But such a Zero-space and Zero-time are

inconceivable. The absolute Nothing , having neither Space

in which to put itself nor Time in which to endure, cannot

exist by itself. And if it cannot exist in its uniqueness,

it exists in multiplicity, bound to the Everything in the

Nothing-Everything.

In the spirit of the dialectic

Equilibrium which governs the Universe, each affirmation is

confirmed by its negation. On the other hand, is not the

Nothing-Everything confused with the Nothing? During my

adolescence these thoughts lived in me like grotesque

characters from a novel. I even tried, with laborious

reasoning, to empty the world of all Creation; however, when

nothing was left, there remained Space, the marvellous

container impossible to reject, impossible to eliminate by

any stretch whatsoever of the imagination. And I was

astonished to perceive in the impenetrable Nothingness,

which should have had supreme priority over all Creation, a

divine symbol, a fascinating purification of the world in

the absolute.

Its impossibility to exist by itself

seemed to weigh on the Cosmos like a kind of “original sin”,

in a continuous expiation, in the alternative

existence-non-existence. In all things one realized the

sense of annihilation, even in the supreme moments of

spirituality, love, contemplative ecstasy… Almost as if it

were Nothingness which imposed itself on all the Cosmos, on

all this universal Tower of Babel, built on contrasts as the

only thing better-defined: as dialectical Equilibrium, like

a kind of metaphysical Consciousness. It is upon this Spirit

of Equilibrium – I thought – that everything is constructed

and is destroyed in Nature.

The Everything in Nothingness, one thing

within the other, from the spasm of hunger to the quivers of

love or death, all things seemed to be dominated by the

longing to fill a void, by the desire of one half of the

world to devour the other half in order to live, so as to

exist.

The Universe is eternal, without

beginning, but given - as the fundamental rule – that the

first element which anything requires in order to exist,

even Nothingness, would have found a Space in which to put

itself, there is in nature itself the irresistible need for

one thing to interpenetrate another: the need, that is, for

Movement, the eternal law of creation and of life. On the

other hand, to put or to remove, to be born or to die, must

all be one for the impartial Equilibrium which can only

mingle, ad infinitum, the one within the other, in order to

arrange things.

A continual flight, protest against any

definite thing. This formula of One-thing-into-another, so

puerile as a principle, does not clash with the other

fundamental laws of nature. All these laws tend to be as

close as possible to the insignificant, to the Nothingness.

Everything tends to escape, to evade

reality. This is also seen in the continual transformation

of things. A wood destroyed by fire, swallowed by

earthquakes, by other cataclysms, by thousands of years,

becomes coal and petroleum, it burns, evaporates and so on,

following the eternal principle of “not being that which it

is”. Also time reflects Nothingness with its present which

has hardly appeared when it becomes the past, and with its

elusive future.

“ Is it possible”, I asked myself, “ that

the same grotesque sort of existence for Nothingness happens

to such an extraordinary Creation as it does to each created

thing?”

In those years of fanciful meditations, I

imagined space made up of an infinity of small dots which

continually rummaged in themselves in search of the smallest

possible one. They were like spirals which clung together

increasingly more frenziedly, more dizzily, converging

towards an ever smaller space. Close to the untouchable

Nothingness they exploded and returned in the opposite

direction towards a larger space where they were immediately

absorbed by the other, stronger convergent spirals. The

spirals, clashing and converging among themselves,

undifferentiating the various degrees of density and

strength of space, in the end wove matter. I thought that

they had always existed in space and that new solar systems

like our own, continued to be formed.

These were not arguments which intended

to undermine religious opinions – faith is a sentiment of

the soul which one possesses with an authentic echo of

oneself.

Certain peoples have a religious vision

of Nothingness. For an Indian, for example, as the poet

Tagore told me in 1936, Nothingness is almost a sacred word.

It is impossible to explain these things to a Westerner.

The present does refute time, as in certain Indian temples,

and the soul tends to raise itself within the Infinite, in

the yearning for the Inexistence.

Even considering the East nearest to us,

it is not easy to describe the sense of metaphysical

emptiness which is created around the voice of the “

muezzin” as soon as he invokes “ Allah u Akbar” ( God is

great), calling the faithful from the summit of the mosque

to their humble prayers. And with such few notes, with so

much harmonious musicality:

How many times, before painting a

landscape from life, I have been overwhelmed by this emotion

which gives the infinity of the heavens. I would focus on a

distant point and then, using my imagination, I would move

my glance towards a still more distant point – and so on –

until I finally lost myself in the ecstasy of a new

sensation, transcendent.

And since I knew that, from light to

colours, from sounds to ultrasounds, every thing in nature

was organized on the intensity of waves, it seemed I was

tuned to a metaphysical wave length in Nothingness, in the

Infinite. It seemed to me that I had escaped myself, and I

intuited that there is the magical reflection of the before

and after life in us. And that Nothingness is precisely the

ideal to which each life unconsciously aspires. Also in

order to think profoundly of God, to express my humility in

prayer, I had to make a certain void in myself, annul every

egoistic instinct, to start out from emptiness, from

Nothingness. I seemed to be like a bird which had to flap

its wet wings before flying. Only by making a void in

myself, could I approach the mysterious divine Spirit more

closely, the unknown force which appeared masked by

Nothingness.

Christian martyrs, anchorites, Indian

santons and Zen followers have found the best moments of

their thought and faith in the absolute search of the beyond

of existence, in the sublimation of emptiness. Of that void

which commence with deep respiration of the mind and has

always something new, fresh as in the phenomena of nature,

something which lightens the banal pressure of life.

Perhaps by intercepting a fluid lost from this mysterious

Nothingness made physical, man goes beyond himself, he

approaches the ideal of attuning himself with the sublime

in a supreme God who annihilates the absurdity of the

Nothingness-Everything.

I learnt from Epictetus’s Manual, which is

a sort of moral summary of Stoic philosophy, to practice ataraxy. In Paris, as I have already said, at the time when

I attended the Académie des Beaux-Arts Julian, I alternated

my studies with lessons which I gave to various pupils at

their homes. In those years many parents preferred not to

send their daughters to the Académies and so, in often

having to move about, sometimes from one end of Paris to the

other, during these long trips I would practice ataraxy. I

reached the point of immersing myself in a serene state of

mind, safe from any external disturbance; I only allowed

myself to be influenced by things determined by me (state of

mind, opinions), and I ignored everything else which did not

depend on me, since it was outside myself. I conditioned

myself by way of two stages:

1 – Control of the state of mind in an

imaginary circle of isolation and defense;

2 – Control, within a larger circle, of

that which could infiltrate the area already controlled.

Subsequently, intensifying the

concentration after these two stages which produced ataraxy

in me, and going beyond the second circle, I reached the

point of confounding this state of mind with Nirvana, with

Nothingness. But here it was already “transpresence”, a sort

of void as it is referred to in the East, which I was to

discover better some years later. The vaster area of

perception around the mind, the more the latter is elevated.

This control is like a growing pressure which digs deeply

into our being. All of this, however, depends on an

ever-intensifying concentration.

With these three stages of concentration,

I gradually guided myself to Subform painting.

My practice was very different from the

ataraxy of the ancients Stoics (which also led to

insensibility and egotism). I had only to be subjected to a

control of myself, selecting my sensations. I thought with

greater lucidity, I was less a slave to things and I was

proud of profound by feeling the meaning of the Delphic

precept: “ know yourself”. In 1932, however, I received an

unexpected and violent shock which made me understand, in a

concrete way, our degrading reality: the Absurd. This was

the death of one of my pupils. One Saturday afternoon,

while I was going to her house for our lesson, I noticed –

and what horror the realization gave me later – that I was

humming the hackneyed theme of Chopin’s ‘Funeral March’. I

rang the doorbell and a person I had never seen before opened

it. Everything seemed strange; even the entrance was

plunged into darkness, while only a few days before, at the

previous lesson, the girl herself had let me in, as she

usually did.

“ I’m the painting teacher,” I said to

the unknown man. Then I heard a strangled, mourning voice:

“She was buried yesterday… Typhus…”

Alone, in the street, with the obsessive

Chopin still in my ears, I began to understand. I was

overcome by a deep torment and realized - only then – that

I had been truly fond of that girl who had been my pupil for

almost a year. The next day, in a small office at the

entrance of the cemetery where I went to find her, I

received a ticket with the number of the sector, the row and

the tomb… I found her name on a small rectangle of earth

which had just been dug over, and I left the first roses I

had ever given to a girl. In that deserted corner of the

cemetery – to which I often returned – and in the peace of

all those souls, something ineffable united me with them.

A profound change took place in me. My poor philosophy

became concrete not in order to accept death – and even

today I refuse this idea – but rather the Absurd,

Nothingness. In the deep silence which interpenetrated

everything, my thoughts became more acute. I even seemed to

perceive the petals’ farewell which detached themselves

sorrowfully from the roses, while I once again saw sweetly

within me that person and contemplated her luminous eyes,

her hands by way of the earth and flowers which covered her.

It was the first time that I had found

myself in front of this other face of human destiny and also

afterwards, during my solitary life without relations or

patrons of any sort, and without a country of my own, not

only did I remain detached from death and cemeteries, but

perhaps also from my own life.

I suddenly realised that reality was

conditioned and that Nothingness was the true key to all

things. Faced by those graves I asked myself whether

Inexistence, Nothingness were the precious ideal to which

each human being unconsciously aspires, and which we have

lost in the vortex of life. Maybe we only join one another

in death? I found it right that God should be the substance

of Everything, as also of Nothingness and that our destiny

be also His…

What can it mean – I asked myself – to be

beautiful and to be good, ugly and bad, when everyone

suffers and dies in the same miserable way? Or, perhaps, the

epitaph which would be appropriate for each one of us is

engraved on the forehead of the great Jupiter: Mort ou vif ,

Méchant ou bon, j’ai un seul nom: Contradiction…

I believe I wrote these lines, in fact,

at the exit of the cemetery in one of those peaceful cafés

which one existed – familiar homes of so many ‘solitaries’.

After this sad event I felt more than

ever disgusted by the environment in which a painter had to

make his way.

I decided to leave Paris. The Orient

attracted me and I took the opportunity of going to Egypt

where I painted important portraits. On arrival, some time

later, I discovered in Khartoum “transpresence” which I

derived from ataraxy. In order to isolate myself better in

my work, intensifying the concentration, I reached the point

of completely excluding what surrounded me, of reducing all

things to Nothingness. And when, after various efforts, I

also succeeded in attuning myself to the emptiness which I

made in myself, I began to paint.

Only in this way did I succeed in

finishing my commitment to Abbas Pascià for a whole series

of paintings which were to adorn his villa. The tropical

heat oppressed me and, moreover, I found myself in the

pre-war East and with all its comfortable precepts of life,

its fatalism and its famous “ Maàlesci” (everything’s

fine).

In the quarter where I was living, from

morning to night one only heard indigenous music; if at

first it annoyed me, I was soon so taken by it that I set

about studying it in earnest. These were ingenious chants

which conveyed laziness and languor; I realized how well–founded were

Aristotle's writings about the influence of

music on character and how right was ancient Greek law which

prohibited certain music. The environment had a negative

influence on me. I decided only to paint at night, using

large portable lamps (“à kabrit”) common in the East. And

here I began to prepare my colours on a large table with the

top transformed into a palette; also the canvases were

placed horizontally. When the accumulations of colours, the

lamps and all my other necessities were arranged, I took a

large flat brush with short bristles (so that I could also

use its metal ring) and, ready to paint, I concentrated on

isolating myself in the transpresence. In that environment,

unsuited to my painting, I had to make a great effort to

obtain this spiritual independence, and it was by way of a

certain reaction that I started my work, as soon as I

reached transpresence. Thus, before painting, not only was

the resentment and the confusion by which I was surrounded

cancelled from my mind, but once again manifested in me –in

my passion for art- were new and strong impulses. I

acquired the habit of often working at night, always in

this way, and the ease with which I could by now immerse

myself in the transpresence, which gradually exploded more

deeply, more than once gave me real interior satisfaction.

Later in India I came to know numerous

devotees of Zen and the Mandala and I was surprised to find

myself no less initiated than they were to the void, besides

the religious interpretation. Perhaps it was for this

reason that U Thant ( who before becoming UNO Secretary

General was also a Buddhist monk) with his enigmatic smile,

called my way of achieving emptiness "Zen-Sécan”, finding

it very personal. This self-contemplation of mine before

painting, coincided at certain points with philosophical

disciplines which had spread from China to India and Japan,

to hundreds of school and convents.

They taught, and still teach, principals

which are appropriate for the self-development of one’s

spiritual and physical faculties, with a gradual

accumulation in oneself of the maximum of psychic energies.

After long periods of training, one reaches

ever-increasing concentrations of repressed energies which

profoundly bear upon the elevation of thought in action and

on its lightning rapidity. For this reason, Zen is even

taught in gymnasiums in order to give athletes a better

awareness and mastery of their own forces. For example, in

archery (“Kyudo”), before shooting an accurate accumulation

of psychic forces, to be freed together with the loosed

arrow, is required. This principle of suspending action in

order to augment a liberated force convinced me more and

more that everything was generated in the contrast between

two opposed forces. Everything was connected to the

principal and creative spirit of the dialectical

Equilibrium. I realized that in Calcutta and Hong Kong the

sort of Zen and Zazen taught with recourse to notions of

emptiness in order to see better into oneself, was not far

from my way of identifying “myself” through that which is “beyond myself”. Also, through a sort of metaphysical

lucidity, I saw myself transported from the tranquil state

of mind of ataraxy to what I had called “the state of being

beyond myself” or transpresence. This new dimension, which

surpassed the depth of being, irradiated me in a space which

was beyond myself. Once I had entered into this

metaphysical state, in the acquisition of consciousness of

the soi-autre which makes the soi-meme so

precarious – so common – I not only had at my disposition

that psychic energy which accumulated in me, but also that

which surrounded me. And it was then that I perceived a

surplus of life which became sublimated in the agreement

between “me” and the “not-me”, transforming me – body and

spirit – into a single impulse: my being and the palette

became one and the same.

Still in India, in Calcutta, in 1941, one

of the most extraordinary event in my career as a painter

happened to me. One evening I returned home late. Before

going to bed, I noticed that my palette still had to be

cleaned. I had prepared it in the afternoon, ready for work,

thinking I would return early. Despite the fact that the day

had been very tiring, I decided to paint.

I set about concentrating myself as usual

but, as I was very tired, I did not succeed in keeping myself

in the transpresence: I lost it as soon as I touched the

colours. It was impossible for me to make the two efforts

simultaneously. It was in this way that, by compelling

myself to a more intense concentration, I completely lost

the idea of myself. I do not know how much time passed…

Suddenly I felt a tremor. It was a window

which was banging violently. And that brought me back to

reality. It seemed to me that I had momentarily slept:

although disturbed, I realized that instead I had painted

and in a state of deep trance.

I looked with astonishment at my fingers

covered with paint and at a large half-filled canvas. I did

not know what to think. The style of the painting was not

mine at all!... It was more alive, more dynamic than the

painting I had done in Khartoum affected by the state of

transpresence. I burst out laughing and felt relieved. “This time I have exceeded myself,” I said. “ I have just

returned from a life which is very different from mine”.

The half-painting was there, all vibrating with new forms

and colours in the full light. But I felt a deceitful

tiredness never experienced before. In the morning, when I

looked more carefully at the painting, I was enthusiastic.

The technique and the “fantasy” of the work were of a

clarity and originality which were unknown to me. I thought

that the too prolonged transpresence the evening before had

excluded me completely in order to make room in me for a

basic–subconscious, primitive which, continuously repressed

by our civilization, has not been mirrored in us for

millennia. I said jokingly to myself:” I have received a

visit…. Perhaps one of my ancestors came to see the most

recent creation of his progeny”.

I have always been attracted by

anthropology. I have tried, more than once, to imagine the

features and life of an hominid, of a man lost in the dawn

of time, of an ancestor to whom I owed my life.

I do not know why, but I showed this new

painting, still wet, to my barber and to other acquaintances

in the neighbourhood. They did not like abstract art

although I felt they were sincere in their admiration of

it. It was almost as though it touched a secret spring in

them – which is common to us all – the sub-subconscious. I

was certain that I had once again found an ancient and lost

awareness, that of archaic man faced by his simple and

primitive subconscious, more real that our own. I realized

that my pictorial alphabet had been enriched by new signs,

new forms and that that strange painting was a projection of

my subconscious.

This was why I thought of calling it “

subform”.

For two or three weeks I waited for the

evening to once again try to find the same creative impetus

in my oblivion. I persisted in attempting to relive each

moment preceding that singular trance. But I no longer

remember anything of importance apart from the decision I

had taken of immersing myself as far as possible in the

transpresence. I disappointedly realized that it was

impossible to find that kind of sub-subconscious painting

again, and I thought that it was precisely my instinct of

self–preservation, if not an unwitting prudence, which was

keeping me away from that “no man’s land”. Maybe I was

afraid to go back into that state of trance, to the limits

of being. Thus many days passed during which I was unable to

paint. Since for some time I had already intended to go to

new Delhi, I suddenly decided to leave. I was always

interested and enthusiastic when I could say :” I’m leaving

tomorrow!...”

It gave me an invigorating sense of

freedom. It was a recommencement, and when I felt the

monotony of my solitude, to leave meant to immerse myself in

a new life. Although “tomorrow” in India also means “never”, like the ironic “bukra” of Egypt.

Chance, that fanciful sprite which may

also play tricks on the disciplined severity of our cosmos,

which arranges and upsets our affairs, had me leave only

three months later because, and in the most unexpected way,

I rediscovered subform painting. I dedicated the day before

my departure to quick, last minute purchases. It was

already evening and I still had to say good-bye to some

acquaintances, including a picture framer. I thought that

he was the least important visit and that I would be able to

get through with it quickly, as was the case, although in

fact it turned out to be an extremely important visit.

The picture framer lived in an old house

in which, behind a main door, one had to go down a dark

narrow staircase and along his workshop-cum-frame deposit

which led to the basement. This finally opened onto a stone

staircase which had walls covered with drawings.

All of this complicated itinerary for an

almost useless visit ended up by exasperating me and I

hurried to go up the steps three at a time, freeing my right

hand as best I could from the packages with which I was

laden. My hand was lifted ready to knock as soon as I

arrived at the floor on which he lived, the fourth or fifth,

but at that moment I found it was inexplicably impeded and

held immobile. For a second I had the sensation of I don’t

know what, which was familiar and similar to another

interrupted movement. With my eyes fixed on that stiff arm

I suddenly remembered a detail which the trance of that

extraordinary evening had made me forget. The extreme

tiredness of that day had not allowed me, like other times,

to maintain the state of transpresence parallel to the

painting. Exhausted, almost in spite of my useless efforts,

and resigned by then to throwing away the paints, I had made

a firm decision: to maintain the transpresence for a short

time without allowing it to connect automatically with the

impulse to pain. I also remembered the tense arm which could

be restrained with difficulty in the effort of stopping

myself from making whatever movement, notwithstanding the

increasingly insistent pressure of the void.

Now, in front of the picture framer’s

door, which was still closed, I felt in me something like an

enlightenment; I seemed to become connected with the

infallible mechanism which led to the sub-subconscious. I

firmly believed in the force of the contrast which was the

creator of necessity, the universal basis of everything, of

our existence and of our civilisation.

Optimist by nature – as unfortunately I

still am, and too much so – I had the certainty that I had

discovered how to achieve a new painting. I went slowly

down the stairs. Everything seemed to be transformed. Even

the basement which led to the exit seemed to be more typical

than ugly. That evening I felt more immersed than ever in

the magical atmosphere of Calcutta, city of miracles. I

went to sit in the first café which I happened to find. In

that noisy little native meeting-place, in front of the

radio which gave out the latest news at full volume, I

decided to postpone my departure.

Painting was everything to me. In that

war period the Indian atmosphere was more that ever hostile

to Europeans. It was a diffidence which saddened me. I

felt instinctively close to the Indians and was conscious of

their rights and problems.

It is in these solitary and repressed

moments of life that the artist feels the most need to take

refuge in what he loves, in what he feels most deeply. He

tends to surpass himself in the desire to transform, to

create, to reflect himself in a new being, in a more

integral presence, beyond the “walls” of time.

Returning home, I thought at lengths of

how to prevent myself from being overwhelmed by the trance.

This time I was more afraid of the consequences which it

could cause me. On the other hand, I seemed to be going to

find a new Land, unknown, and that made me stronger. Having

returned to my room, I did not feel like concluding the

evening. Everything seemed extraordinary to me. I prepared

the lamps, took out the powders, the oil, and what was

necessary in order to mix my colours, remaining a little

detached from everything I did; I even remained detached

from myself, so alive in me was the intention of escaping

from things, of watching myself from a distance… I was

spurred on by the certainty of succeeding in once again

finding that new form of painting with such a profound and

luminous touch. I had the presentiment of deciphering a

whole secret world still alive in us, of being reborn

through art into a new dimension – more authentic,

essential, metaphysical. Although at the same time

something strange overcame me. I was afraid. A

profound, insidious fear, the fear of being swept away by a physically and mentally

risky experience.

In my often adventurous past I had

overcome ugly moments courageously but that evening I am

sure that I was really face to face with fear.

As usual, when the preparations were

completed, with the brush ready in my hand and everything

spread out in front of the palette, I began to concentrate.

Trying to repeat what I remembered of that far-off evening,

I forced myself to resist to the utmost my by now engrained

habit of starting to paint as soon as I had achieved the

transpresence. I had to force myself for a long time to

detach myself from reality, while at the back of my mind,

with my heart which I almost felt beating, I every now and

again felt a recall to prudence… I was in the vortex of two

equally strained opposites. The more the state of

transpresence intensified, the more difficult it was for me

to restrain the impulse of my arm to paint. Thus, while on

the one hand I proceeded, enveloped in the hermetic cloak of

the transpresence, in the grip of an increasingly greater

concentration, on the other I refused the almost automatic

impulse to paint, that profoundly acquired function

predetermined by the transpresence itself. It was like the

play of a spring which contracts and is then released, like

the increasingly growing alternation between receptivity and

reaction.

Little by little, I became

depersonalized, in a semi-hypnotic state, in the abstraction

of myself. Suddenly I had the sensation that everything in

me was blocked. I felt a moment of suspense!

Everything seemed magically to have

changed, and all of a sudden I realized that I was already

painting. A superhuman emotion brought me to the canvas, to

a mad palette and to a powerful hand which searched within

the open veins of the colours. It was not “ painting”, it

was existing in a new and more authentic dimension – it was

“ being”. I was no longer painting, I was creating,

substituting “doing” with “creating”. I was no longer

afraid. In the explosion of those frenetic, flushing

energies of painting, there was the accumulated anger of a

thousand repressed ancestral fears. I decided I would

always paint in that way. I was guided by a new dynamic,

which had its genesis in far-off times. This was reflected

by sudden energies in my process of painting which,

however, always corresponded to the rationality of my well

acquired craft of the painter which is, after all,

closer to the subconscious than to the will. Moreover, it

seemed that each brush stroke was in itself a point of

departure and of arrival, that it was born already complete,

it was so determinant. I realized that in the depths of our

being we are less the man of today than the homo semper,

a still green branch of the hominid. It is in this way that

the dynamics of my paintings are determined by this basic

instinct which drives me to the canvas to project that

throb of mysterious life which was once ours. In my

painting there is the significance of impulses and also of

messages which are not of our common subconscious, but of a

sub-subconscious, of that archaic one which affirmed itself

in us for millions of years and which we then repressed.

When I paint subform pictures I feel completely lost in

another world. The liberation of the impulses of the

profound instinct determines the presence in me of a

superior force, direct and uncheckable, which is freed by

painting. It is such a concentrated metaphysical dynamism

that it removes me from myself and from my way of doing

things, and transmits unknown and unlooked-for forms and

figures which, however, excite in me the affection which one

feels once again on seeing long-forgotten familiar people

and places. Often creations are born on the canvases,

perhaps reflections of realities lived long ago, which later

prompt me to be completed or corrected with some brush

strokes. Hence, the transcendency of the gesture which tends

towards the essential, the decisive and absolute touch which

reduces forms to the minimum, the impetus and passion which

overwhelm me, become fundamental elements of the technique

and spirit that the sub-subconscious imposes on me, taking

possession of me. My hand, my way of painting, my painting

experience, and also sometimes the reflection of a haunting

imagination or a recent impression, are also subjected

within the frenzy of the action to an instinctive force and

a metaphysical sense unknown to me. Immersed in a state of

semi-trance, perhaps suspended on a delicate thread of

awareness which keeps watch, which does not allow me to be

completely carried away, I look beyond reason and the

senses. I draw upon impulses, new and vitalizing energies

in that dimension which I could define as the “beyond” of

myself. It would be humiliating and useless to fill the

canvas with the well-known reflections of the man of today,

with his banal and unconscious impulses of repetition. I

leave my painter’s talent in the hands of a more natural

being, more resolute and without complexes.

In the subform, “creating”painting is different

from “doing”, also because the “doing” presupposes the

intention of carrying out something which one has in mind,

which one already knows, whereas “creating” is the “doing”

without knowing what the result will be. Life owes itself

to a sense of creation which excludes the intention of

doing: our living bodies of flesh were neither made nor

constructed, but came from a metaphysical Spirit which

induced matter to create life. Also the artist almost

always creates under the effect of a stimulus, of an

emotion, a reaction. Rossini found inspiration for his

compositions after enjoying his table, and Schubert in a

girl’s glance. Balzac stimulated his imagination in dozen

of cafés, and Michelangelo worked under the impetus of a

frenetic aggressiveness, connected, perhaps, periodically,

to his sub-subconscious. Sometimes, while I paint, I have

the sensation of vague and impatient shadows which are

latent in me, and as soon as these take on form and

character in the play of colours, I feel a singular

exaltation. This makes me believe that in my

sub-subconscious there is still a magma, still alive, of

repressed images. Painting has become for me more than ever

a psychic necessity which in the disposition of new forces

makes me aware of a more authentic life. In excluding

myself with meditations prior to entering the state of

transpresence, in the exaltation of Nothingness, I come

close to that truer and purer reality which was once ours.

Certainly one will never be able to once again find that

vitality which once existed, the authentic sense of

existence, of the metaphysical, which only illuminates us at

times. There is, for example, something profound and

fundamental which “starts” in my heart every time that my

glance meets that of my daughter. All the enquiring

tenderness that little Laura puts into her eyes excludes and

transcends man, distorted and deformed by a totally false

and conventional life. In those moments I realize that we

are always more subjected by conscience-comfort, by the

matter which we perfect and train to our service. We

objectify ourselves, we characterize ourselves in relation

to the objects which we believe we possess but which, after

all, possess us in the paralysing object-man monologue. We

do not realize that the triumph of matter is in direct

relationship to our decadence and that by dint of being

determined becomes determinant, and indeed it already tries

and condemns us…

These hands of ours, able and astute

tools as Shakespeare called them, must in their incredible

past have accumulated an immense store of knowledge and

skill. It was, perhaps, in order to free them that the

hominid chose the erect position. And who knows whether it

is not our hands’ prehensility and instinctive memory which,

indirectly, led our brain to receive ideas, to drive it to

the game of thinking and of the will, that basic

characteristic of man.

|